By James Forshaw, Project Zero

I've been spending a lot of time researching Windows authentication implementations, specifically Kerberos. In June 2022 I found an interesting issue number 2310 with the handling of RC4 encryption that allowed you to authenticate as another user if you could either interpose on the Kerberos network traffic to and from the KDC or directly if the user was configured to disable typical pre-authentication requirements.

This blog post goes into more detail on how this vulnerability works and how I was able to exploit it with only a bare minimum of brute forcing required. Note, I'm not going to spend time fully explaining how Kerberos authentication works, there's plenty of resources online. For example this blog post by Steve Syfuhs who works at Microsoft is a good first start.

Background

Kerberos is a very old authentication protocol. The current version (v5) was described in RFC1510 back in 1993, although it was updated in RFC4120 in 2005. As Kerberos' core security concept is using encryption to prove knowledge of a user's credentials the design allows for negotiating the encryption and checksum algorithms that the client and server will use.

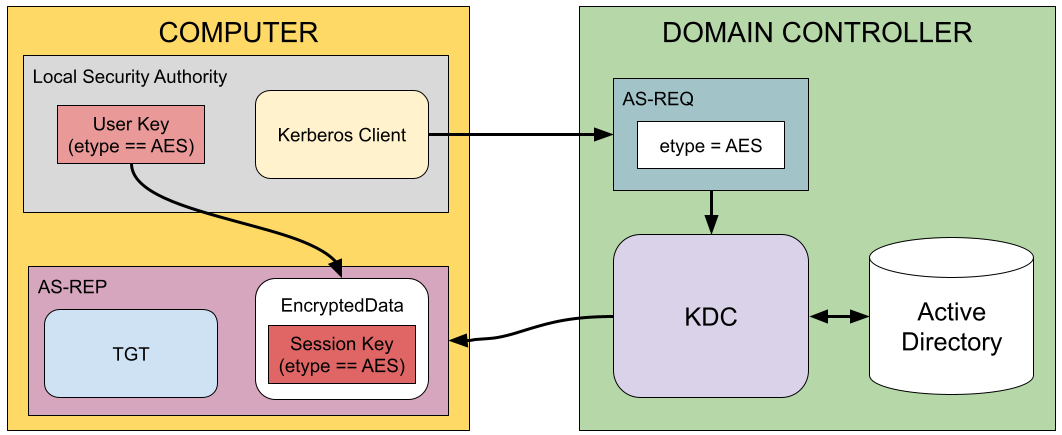

For example when sending the initial authentication service request (AS-REQ) to the Key Distribution Center (KDC) a client can specify a list supported encryption algorithms, as predefined integer identifiers, as shown below in the snippet of the ASN.1 definition from RFC4120.

KDC-REQ-BODY ::= SEQUENCE {

...

etype [8] SEQUENCE OF Int32 -- EncryptionType

-- in preference order --,

...

}

When the server receives the request it checks its list of supported encryption types and the ones the user's account supports (which is based on what keys the user has configured) and then will typically choose the one the client most preferred. The selected algorithm is then used for anything requiring encryption, such as generating session keys or the EncryptedData structure as shown below:

EncryptedData ::= SEQUENCE {

etype [0] Int32 -- EncryptionType --,

kvno [1] UInt32 OPTIONAL,

cipher [2] OCTET STRING -- ciphertext

}

The KDC will send back an authentication service reply (AS-REP) structure containing the user's Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT) and an EncryptedData structure which contains the session key necessary to use the TGT to request service tickets. The user can then use their known key which corresponds to the requested encryption algorithm to decrypt the session key and complete the authentication process.

This flexibility in selecting an encryption algorithm is both a blessing and a curse. In the original implementations of Kerberos only DES encryption was supported, which by modern standards is far too weak. Because of the flexibility developers were able to add support for AES through RFC3962 which is supported by all modern versions of Windows. This can then be negotiated between client and server to use the best algorithm both support. However, unless weak algorithms are explicitly disabled there's nothing stopping a malicious client or server from downgrading the encryption algorithm in use and trying to break Kerberos using cryptographic attacks.

Modern versions of Windows have started to disable DES as a supported encryption algorithm, preferring AES. However, there's another encryption algorithm which Windows supports which is still enabled by default, RC4. This algorithm was used in Kerberos by Microsoft for Windows 2000, although its documentation was in draft form until RFC4757 was released in 2006.

The RC4 stream cipher has many substantial weaknesses, but when it was introduced it was still considered a better option than DES which has been shown to be sufficiently vulnerable to hardware cracking such as the EFF's "Deep Crack". Using RC4 also had the advantage that it was relatively easy to operate in a reduced key size mode to satisfy US export requirements of cryptographic systems.

If you read the RFC for the implementation of RC4 in Kerberos, you'll notice it doesn't use the stream cipher as is. Instead it puts in place various protections to guard against common cryptographic attacks:

The encrypted data is protected by a keyed MD5 HMAC hash to prevent tampering which is trivial with a simple stream cipher such as RC4. The hashed data includes a randomly generated 8-byte "confounder" so that the hash is randomized even for the same plain text.

The key used for the encryption is derived from the hash and a base key. This, combined with the confounder makes it almost certain the same key is never reused for the encryption.

The base key is not the user's key, but instead is derived from a MD5 HMAC keyed with the user's key over a 4 byte message type value. For example the message type is different for the AS-REQ and the AS-REP structures. This prevents an attacker using Kerberos as an encryption oracle and reusing existing encrypted data in unrelated parts of the protocol.

Many of the known weaknesses of RC4 are related to gathering a significant quantity of ciphertext encrypted with a known key. Due to the design of the RC4-HMAC algorithm and the general functional principles of Kerberos this is not really a significant concern. However, the biggest weakness of RC4 as defined by Microsoft for Kerberos is not so much the algorithm, but the generation of the user's key from their password.

As already mentioned Kerberos was introduced in Windows 2000 to replace the existing NTLM authentication process used from NT 3.1. However, there was a problem of migrating existing users to the new authentication protocol. In general the KDC doesn't store a user's password, instead it stores a hashed form of that password. For NTLM this hash was generated from the Unicode password using a single pass of the MD4 algorithm. Therefore to make an easy upgrade path Microsoft specified that the RC4-HMAC Kerberos key was this same hash value.

As the MD4 output is 16 bytes in size it wouldn't be practical to brute force the entire key. However, the hash algorithm has no protections against brute-force attacks for example no salting or multiple iterations. If an attacker has access to ciphertext encrypted using the RC4-HMAC key they can attempt to brute force the key through guessing the password. As user's will tend to choose weak or trivial passwords this increases the chance that a brute force attack would work to recover the key. And with the key the attacker can then authenticate as that user to any service they like.

To get appropriate cipher text the attacker can make requests to the KDC and specify the encryption type they need. The most well known attack technique is called Kerberoasting. This technique requests a service ticket for the targeted user and specifies the RC4-HMAC encryption type as their preferred algorithm. If the user has an RC4 key configured then the ticket returned can be encrypted using the RC4-HMAC algorithm. As significant parts of the plain-text is known for the ticket data the attacker can try to brute force the key from that.

This technique does require the attacker to have an account on the KDC to make the service ticket request. It also requires that the user account has a configured Service Principal Name (SPN) so that a ticket can be requested. Also modern versions of Windows Server will try to block this attack by forcing the use of AES keys which are derived from the service user's password over RC4 even if the attacker only requested RC4 support.

An alternative form is called AS-REP Roasting. Instead of requesting a service ticket this relies on the initial authentication requests to return encrypted data. When a user sends an AS-REQ structure, the KDC can look up the user, generate the TGT and its associated session key then return that information encrypted using the user's RC4-HMAC key. At this point the KDC hasn't verified the client knows the user's key before returning the encrypted data, which allows the attacker to brute force the key without needing to have an account themselves on the KDC.

Fortunately this attack is more rare because Windows's Kerberos implementation requires pre-authentication. For a password based logon the user uses their encryption key to encrypt a timestamp value which is sent to the KDC as part of the AS-REQ. The KDC can decrypt the timestamp, check it's within a small time window and only then return the user's TGT and encrypted session key. This would prevent an attacker getting encrypted data for the brute force attack.

However, Windows does support a user account flag, "Do not require Kerberos preauthentication". If this flag is enabled on a user the authentication request does not require the encrypted timestamp to be sent and the AS-REP roasting process can continue. This should be an uncommon configuration.

The success of the brute-force attack entirely depends on the password complexity. Typically service user accounts have a long, at least 25 character, randomly generated password which is all but impossible to brute force. Normal users would typically have weaker passwords, but they are less likely to have a configured SPN which would make them targets for Kerberoasting. The system administrator can also mitigate the attack by disabling RC4 entirely across the network, though this is not commonly done for compatibility reasons. A more limited alternative is to add sensitive users to the Protected Users Group, which disables RC4 for them without having to disable it across the entire network.

Windows Kerberos Encryption Implementation

While working on researching Windows Defender Credential Guard (CG) I wanted to understand how Windows actually implements the various Kerberos encryption schemes. The primary goal of CG at least for Kerberos is to protect the user's keys, specifically the ones derived from their password and session keys for the TGT. If I could find a way of using one of the keys with a weak encryption algorithm I hoped to be able to extract the original key removing CG's protection.

The encryption algorithms are all implemented inside the CRYPTDLL.DLL library which is separate from the core Kerberos library in KERBEROS.DLL on the client and KDCSVC.DLL on the server. This interface is undocumented but it's fairly easy to work out how to call the exported functions. For example, to get a "crypto system" from the encryption type integer you can use the following exported function:

NTSTATUS CDLocateCSystem(int etype, KERB_ECRYPT** engine);

The KERB_ECRYPT structure contains configuration information for the engine such as the size of the key and function pointers to convert a password to a key, generate new session keys, and perform encryption or decryption. The structure also contains a textual name so that you can get a quick idea of what algorithm is supposed to be, which lead to the following supported systems:

Name Encryption Type

---- ---------------

RSADSI RC4-HMAC 24

RSADSI RC4-HMAC 23

Kerberos AES256-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96 18

Kerberos AES128-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96 17

Kerberos DES-CBC-MD5 3

Kerberos DES-CBC-CRC 1

RSADSI RC4-MD4 -128

Kerberos DES-Plain -132

RSADSI RC4-HMAC -133

RSADSI RC4 -134

RSADSI RC4-HMAC -135

RSADSI RC4-EXP -136

RSADSI RC4 -140

RSADSI RC4-EXP -141

Kerberos AES128-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96-PLAIN -148

Kerberos AES256-CTS-HMAC-SHA1-96-PLAIN -149

Encryption types with positive values are well-known encryption types defined in the RFCs, whereas negative values are private types. Therefore I decided to spend my time on these private types. Most of the private types were just subtle variations on the existing well-known types, or clones with legacy numbers.

However, one stood out as being different from the rest, "RSADSI RC4-MD4" with type value -128. This was different because the implementation was incredibly insecure, specifically it had the following properties:

Keys are 16 bytes in size, but only the first 8 of the key bytes are used by the encryption algorithm.

The key is used as-is, there's no blinding so the key stream is always the same for the same user key.

The message type is ignored, which means that the key stream is the same for different parts of the Kerberos protocol when using the same key.

The encrypted data does not contain any cryptographic hash to protect from tampering with the ciphertext which for RC4 is basically catastrophic. Even though the name contains MD4 this is only used for deriving the key from the password, not for any message integrity.

Generated session keys are 16 bytes in size but only contain 40 bits (5 bytes) of randomness. The remaining 11 bytes are populated with the fixed value of 0xAB.

To say this is bad from a cryptographic standpoint, is an understatement. Fortunately it would be safe to assume that while this crypto system is implemented in CRYPTDLL, it wouldn't be used by Kerberos? Unfortunately not — it is totally accepted as a valid encryption type when sent in the AS-REQ to the KDC. The question then becomes how to exploit this behavior?

Exploitation on the Wire (CVE-2022-33647)

My first thoughts were to attack the session key generation. If we could get the server to return the AS-REP with a RC4-MD4 session key for the TGT then any subsequent usage of that key could be captured and used to brute force the 40 bit key. At that point we could take the user's TGT which is sent in the clear and the session key and make requests as that authenticated user.

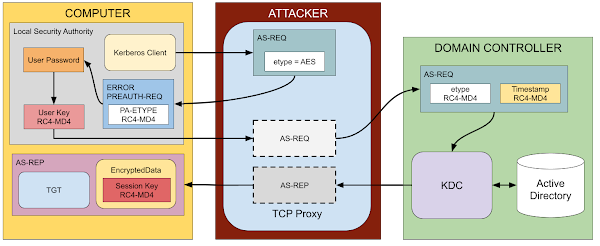

The most obvious approach to forcing the preferred encryption type to be RC4-MD4 would be to interpose the connection between a client and the KDC. The etype field of the AS-REQ is not protected for password based authentication. Therefore a proxy can modify the field to only include RC4-MD4 which is then sent to the KDC. Once that's completed the proxy would need to also capture a service ticket request to get encrypted data to brute force.

Brute forcing the 40 bit key would be technically feasible at least if you built a giant lookup table, however I felt like it's not practical. I realized there's a simpler way, when a client authenticates it typically sends a request to the KDC with no pre-authentication timestamp present. As long as pre-authentication hasn't been disabled the KDC returns a Kerberos error to the client with the KDC_ERR_PREAUTH_REQUIRED error code.

As part of that error response the KDC also sends a list of acceptable encryption types in the PA-ETYPE-INFO2 pre-authentication data structure. This list contains additional information for the password to key derivation such as the salt for AES keys. The client can use this information to correctly generate the encryption key for the user. I noticed that if you sent back only a single entry indicating support for RC4-MD4 then the client would use the insecure algorithm for generating the pre-authentication timestamp. This worked even if the client didn't request RC4-MD4 in the first place.

When the KDC received the timestamp it would validate it using the RC4-MD4 algorithm and return the AS-REP with the TGT's RC4-MD4 session key encrypted using the same key as the timestamp. Due to the already mentioned weaknesses in the RC4-MD4 algorithm the key stream used for the timestamp must be the same as used in the response to encrypt the session key. Therefore we could mount a known-plaintext attack to recover the keystream from the timestamp and use that to decrypt parts of the response.

The timestamp itself has the following ASN.1 structure, which is serialized using the Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER) and then encrypted.

PA-ENC-TS-ENC ::= SEQUENCE {

patimestamp [0] KerberosTime -- client's time --,

pausec [1] Microseconds OPTIONAL

}

The AS-REP encrypted response has the following ASN.1 structure:

EncASRepPart ::= SEQUENCE {

key [0] EncryptionKey,

last-req [1] LastReq,

nonce [2] UInt32,

key-expiration [3] KerberosTime OPTIONAL,

flags [4] TicketFlags,

authtime [5] KerberosTime,

starttime [6] KerberosTime OPTIONAL,

endtime [7] KerberosTime,

renew-till [8] KerberosTime OPTIONAL,

srealm [9] Realm,

sname [10] PrincipalName,

caddr [11] HostAddresses OPTIONAL

}

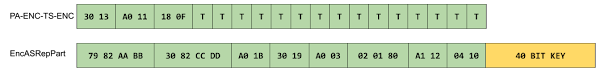

We can see from the two structures that as luck would have it the session key in the AS-REP is at the start of the encrypted data. This means there should be an overlap between the known parts of the timestamp and the key, allowing us to apply key stream recovery to decrypt the session key without any brute force needed.

The diagram shows the ASN.1 DER structures for the timestamp and the start of the AS-REP. The values with specific hex digits in green are plain-text we know or can calculate as they are part of the ASN.1 structure such as types and lengths. We can see that there's a clear overlap between 4 bytes of known data in the timestamp with the first 4 bytes of the session key. We only need the first 5 bytes of the key due to the padding at the end, but this does mean we need to brute force the final key byte.

We can do this brute force one of two ways. First we can send service ticket requests with the user's TGT and a guess for the session key to the KDC until one succeeds. This would require at most 256 requests to the KDC. Alternatively we can capture a service ticket request from the client which is likely to happen immediately after the authentication. As the service ticket request will be encrypted using the session key we can perform the brute force attack locally without needing to talk to the KDC which will be faster. Regardless of the option chosen this approach would be orders of magnitude faster than brute forcing the entire 40 bit session key.

The simplest approach to performing this exploit would be to interpose the client to server connection and modify traffic. However, as the initial request without pre-authentication just returns an error message it's likely the exploit could be done by injecting a response back to the client while the KDC is processing the real request. This could be done with only the ability to monitor network traffic and inject arbitrary network traffic back into that network. However, I've not verified that approach.

Exploitation without Interception (CVE-2022-33679)

The requirement to have access to the client to server authentication traffic does make this vulnerability seem less impactful. Although there's plenty of scenarios where an attacker could interpose, such as shared wifi networks, or physical attacks which could be used to compromise the computer account authentication which would take place when a domain joined system was booted.

It would be interesting if there was an attack vector to exploit this without needing a real Kerberos user at all. I realized that if a user has pre-authentication disabled then we have everything we need to perform the attack. The important point is that if pre-authentication is disabled we can request a TGT for the user, specifying RC4-MD4 encryption and the KDC will send back the AS-REP encrypted using that algorithm.

The key to the exploit is to reverse the previous attack, instead of using the timestamp to decrypt the AS-REP we'll use the AS-REP to encrypt a timestamp. We can then use the timestamp value when sent to the KDC as an encryption oracle to brute force enough bytes of the key stream to decrypt the TGT's session key. For example, if we remove the optional microseconds component of the timestamp we get the following DER encoded values:

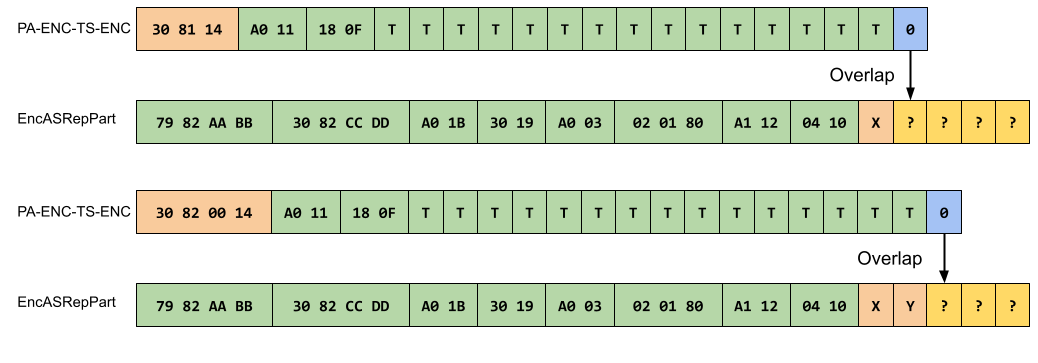

The diagram shows that currently there's no overlap between the timestamp, represented by the T bytes, and the 40 bit session key. However, we know or at least can calculate the entire DER encoded data for the AS-REP to cover the entire timestamp buffer. We can use this to calculate the keystream for the user's RC4-MD4 key without actually knowing the key itself. With the key stream we can encrypt a valid timestamp and send it to the KDC.

If the KDC responds with a valid AS-REP then we know we've correctly calculated the key stream. How can we use this to start decrypting the session key? The KerberosTime value used for the timestamp is an ASCII string of the form YYYYMMDDHHmmssZ. The KDC parses this string to a format suitable for processing by the server. The parser takes the time as a NUL terminated string, so we can add an additional NUL character to the end of the string and it shouldn't affect the parsing. Therefore we can change the timestamp to the following:

We can now guess a value for the encrypted NUL character and send the new timestamp to the KDC. If the KDC returns an error we know that the parsing failed as it didn't decrypt to a NUL character. However, if the authentication succeeds the value we guessed is the next byte in the key stream and we can decrypt the first byte of the session key.

At this point we've got a problem, we can't just add another NUL character as the parser would stop on the first one we sent. Even if the value didn't decrypt to a NUL it wouldn't be possible to detect. This is when a second trick comes into play, instead of extending the string we can abuse the way value lengths are encoded in DER. A length can be in one of two forms, a short form if the length is less than 128, or a long form for everything else.

For the short form the length is encoded in a single byte. For the long form, the first byte has the top bit set to 1, and the lower 7 bits encode the number of trailing bytes of the length value in big-endian format. For example in the above diagram the timestamp's total size is 0x14 bytes which is stored in the short form. We can instead encode the length in an arbitrary sized long form, for example 0x81 0x14, 0x82 0x00 0x14, 0x83 0x00 0x00 0x14 etc. The examples shown below move the NUL character to brute force the next two bytes of the session key:

Even though technically DER should expect the shortest form necessary to encode the length the Microsoft ASN.1 library doesn't enforce that when parsing so we can just repeat this length encoding trick to cover the remaining 4 unknown bytes of the key. As the exploit brute forces one byte at a time the maximum number of requests that we'd need to send to the KDC is 5 × 28 which is 1280 requests as opposed to 240 requests which would be around 1 trillion.

Even with such a small number of requests it can still take around 30 seconds to brute force the key, but that still makes it a practical attack. Although it would be very noisy on the network and you'd expect any competent EDR system to notice, it might be too late at that point.

The Fixes

The only fix I can find is in the KDC service for the domain controller. Microsoft has added a new flag which by default disables the RC4-MD4 algorithm and an old variant of RC4-HMAC with the encryption type of -133. This behavior can be re-enabled by setting the KDC configuration registry value AllowOldNt4Crypto. The reference to NT4 is a good indication on how long this vulnerability has existed as it presumably pre-dates the introduction of Kerberos in Windows 2000. There are probably some changes to the client as well, but I couldn't immediately find them and it's not really worth my time to reverse engineer it.

It'd be good to mitigate the risk of similar attacks before they're found. Disabling RC4 is definitely recommended, however that can bring its own problems. If this particular vulnerability was being exploited in the wild it should be pretty easy to detect. Also unusual Kerberos encryption types would be an immediate red-flag as well as the repeated login attempts.

Another option is to enforce Kerberos Armoring (FAST) on all clients and KDCs in the environment. This would make it more difficult to inspect and tamper with Kerberos authentication traffic. However it's not a panacea, for example for FAST to work the domain joined computer needs to first authenticate without FAST to get a key they can then use for protecting the communications. If that initial authentication is compromised the entire protection fails.